1

There were also many television movies;

we make a lot of them in Canada for the major networks.

I’ve worked for all of them at one time or another.

They involve short, intense assignments, which are

excellent ways of learning the craft because you are in a

constantly changing environment. The

situations—every one is unique—force you to

figure out ways to make things work. That is the great

thing about my job, but it is also the bad thing about

it—you must constantly think about how you’re

going to accomplish what you must achieve.

I have also done a number of TV movies. I

did one ABC miniseries, DreamKeeper, as a second

assistant director, which aired over the course of two

nights in 2003. It was notable for me because it was

among the most difficult shows I have ever worked on. We

had to tell native stories set all over North America.

The logistics were demanding. We had to change tribes,

actors, locations; we had different everything—art

departments, for example—for each tribe.

Scene from the 2003 Miniseries DreamKeeper

In the typical film, the start-up period

tends to be quite difficult because you are figuring how

everything is going to be done and how much time you are

going to take, but eventually, after the first week or

two, you are rolling and you have everything resolved.

But with DreamKeeper, once we would get settled,

we had to completely change everything. We had to

start-up all over, again and again. We had to move across

the province together. In fact, still, whenever people

who worked on DreamKeeper get together, we act

like veterans who fought in a war together. We invariably

end up telling stories about how difficult it all was!

Then there was Brokeback Mountain.

That is undoubtedly the highlight of all of the projects

I’ve worked on, and possibly of all of the projects

that I will ever work on.

How did you learn that Brokeback

Mountain was going to be made in Alberta?

From Tom Benz; he was the [unit]

production manager. I had just returned from Austria,

where I had been working on a production. As soon as I

arrived there was a message from Tom saying he wanted to

arrange an interview. I did not completely understand the

message, so I called him. He explained the situation: he

wanted to bring somebody in to be able to work with

Michael Hausman and Ang Lee so that some of their

knowledge and expertise would remain in the province

after the filming was completed. That would benefit the

film industry in Canada on another level, apart from the

economic advantages and the obvious notoriety associated

with having the film made in Alberta. I was interested,

but there were other candidates for the position as well.

2

So we arranged an interview. I was

slightly jet lagged when I showed up. I’d read the

script, which was phenomenal. That was when I realized

what I could be in for. The opportunity I was being

presented was incredible. I had done some other research.

Of course, I knew of Ang Lee, but I learned more about

Michael Hausman, Scott Ferguson [co-producer, and unit production

manager], and Diana Ossana. I immediately

recognized the caliber, significance, and quality of the

project before me.

“I immediately recognized the caliber,

significance, and quality of the project before me.”

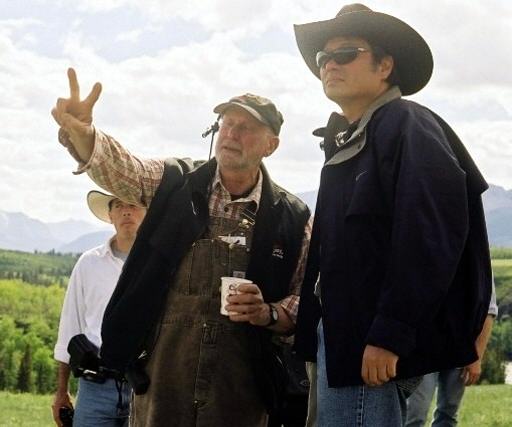

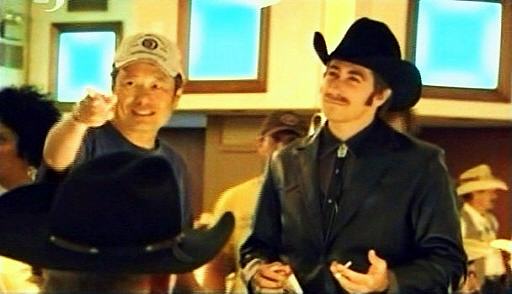

Rodrigo Prieto, Michael Hausman, and Ang Lee

Morley, AB

The interview itself was very

interesting. It’s difficult to describe. Michael

Hausman conducted the interview and it was very casual.

Tom Benz and Scott Ferguson were there. Ang Lee stopped

in to meet me; he was there for only a couple of minutes.

They made me feel at ease right away as they told me

about the project. They were very clear about what they

planned on doing.

I think the reason that I got the job was

that when they asked me if I had any questions, I asked

if they had an idea of what they wanted me to do on the

show. And they were not very clear about that, so they

asked me what I wanted to get from the show. I told them

I did not want to be what is known in the industry as a

“match,” that is, somebody that, under union

rules, they have to hire locally because they are

bringing in an outside person. I didn’t want to

simply show up, put in the time, leave, and pick up a

paycheck. I genuinely wanted to make a contribution. I

did not want to end up a match, which has happened on

other shows with other assistant directors I know.

3

The interview did not last very long,

maybe 20 minutes, and I went home and I told my wife, who

was, of course, very interested. I explained that they

were going to take a couple of days and that there were

other candidates. Tom had told me that they were planning

to discuss it among themselves and then they had to vet

their selection through the hierarchy. So I told her,

“We’re going to forget it ever happened.”

Then, about 20 minutes later I got a call from Tom Benz,

and he said, “They want you.”

“They want you.”

Unit Production Manager Tom Benz

I was overjoyed; an extremely happy day!

And then?

It was not very long; I think it was two

weeks. That just gave me enough time to become a little

more familiar with the script and the cast, and figure

out who was going to be involved. You never really know

when you go into these types of projects what your role

will be. You really can’t know unless you have

worked with everyone before. I did not know Michael

Hausman, Ang Lee, Scott Ferguson, or Michael Costigan [executive producer]at

all, and, since they were my direct supervisors, I

didn’t know what I was in for. It was “ to be

determined.”

I showed up on my first day and it was

then that I realized I was going to be very much involved

in the production. I was handed the script, and the

schedule, by Michael Hausman and was told to do the

breakdown, which is essentially taking the script and

putting it into its tiniest components—for instance,

specifying the trucks that are to be used—in a

program called Movie Magic, which is a computer program

that tracks all of that information regardless of where

you put them in the schedule, and it generates reports

that go to individual departments. Then, in my example,

there are meetings to determine exactly what kind of

trucks, to see what the art department can offer, discuss

the options, and find out what the director expects.

There are lots of meetings: truck meetings, art

meetings, stunt meetings, special effects meetings,

meetings within every department. Oftentimes more than

one department is involved.

4

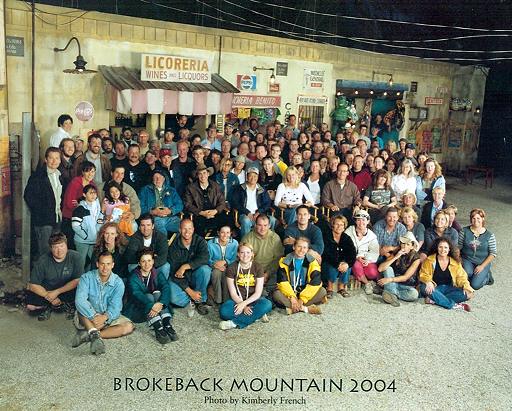

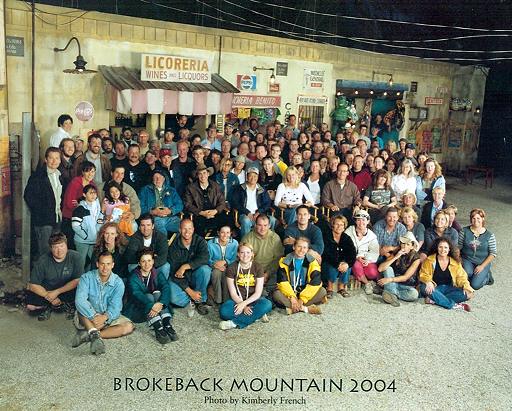

“Hell yes, we’ve been to Mexico!”

Brokeback Cast and Crew Photo Juarez

Alley Calgary, AB

I was given a big part in organizing

those meetings and making sure that everyone got their

time to raise and address issues. So I was very pleased

that from the get-go I was making a contribution. I

certainly wanted the education as well, which was also

great, because Michael Hausman made certain that I was in

his office for all of the high-level meetings with the

executives, actors, and agents. All of the high-level

meetings. I was invited to be a part of, not to

contribute to, but to be there and learn from a master of

film how decisions were made. And I appreciated it, and I

deeply appreciate it to this day. What I learned there

has had a profound influence on the way I do my job

today.

Both Lee and Hausman have had praise

for the professional expertise and craftsmanship they

encountered in Alberta.

Michael Hausman is an instructor at

Columbia [Columbia University, New York City], and I came

to realize that he is a natural born teacher. When you

meet someone who is a natural teacher, you instantly

recognize that they love to connect and share with young

people. That’s the way he is. He volunteered to put

on a master class, in fact he “coerced” Ang,

and Tom, Scott, and Diana, to come up with clips from

their projects. They brought them to a special seminar

and explained their importance, which was unprecedented.

5

Of course we have made many other films

here, but nobody has ever gone to the trouble of putting

on that kind of educational presentation for the film

community here. It was incredibly generous and so very

typical of his approach to filmmaking. So it was not just

us trying to please him. He made a point of giving

something back to the community. Very special.

With whom did you work most closely?

As an assistant director you have to work

with everyone; that is your job. But my direct supervisor

was Michael Hausman. Even though technically the

production manager would be my immediate supervisor,

there was never any question as to who ran that show. Michael

Hausman ran that show. And because of that,

everything, every decision, went through him. Of course,

creative decisions were made by Ang Lee, and script

decisions by Diana Ossana, but every decision went

through Michael Hausman, and the duties I had, everything

I did, came from him.

He made it very easy; he was very

encouraging and he was very generous in letting me do my

job. He could have quite easily made unilateral decisions

regarding just about everything, but he did not. He

always included the production team in those decisions.

He would gather us together and ask our opinions on

anything that came up, and it gave us a good feeling to

be able to contribute. He certainly didn’t have to

run things that way, but he did.

“Michael Hausman ran that show.”

Hausman and Lee Divorce Courtroom

Fort Macleod, AB

6

Can you capsulize what you learned

from working with Michael Hausman?

I think the most important lesson I

learned from Michael Hausman is that our position is

basically one of management. A film is a hard thing to

manage; it is, at best, an artistic endeavor. Especially Brokeback

Mountain, which is one of the purest artistic

endeavors I have ever been a part of. Management does not

just mean the schedule, or the paperwork, or being a good

communicator, or doing all of the basic things properly,

or being thorough. The most important thing about

management is that you are working with

people—producers, crew, cast, artists—and that

you need to hire people to do their best. People look to

leaders to be examples. If people respect who they are

working for, they will give their best.

Michael Hausman opened my eyes. Rather

than adopting authoritative style, he showed me a better

way to manage—by inspiration. That is the best way

to manage. If people are inspired, they will give you

their best. I believe to this day that you can actually

see the difference on the screen. I certainly know that

there are many films that are not run that way, but I

think that the ones that are made by inspiring the cast

and crew have a certain special quality, because people

give that extra bit.

I’ve known and worked with many of

the [Brokeback] crew members for years. Eventually

any crew will start to complain, after working for many

days, lots of long hours, God knows where, in awful

weather conditions. None of that necessarily shows up on

the screen, but it invariably happens. It’s only

natural for crews to grow weary and complain. In Brokeback

Mountain nobody complained.

“In Brokeback Mountain nobody

complained.”

Michael Hausman with Heath Ledger Sheep

Staging Morley, AB

We have done many westerns here, all

sorts of westerns, but in this case there was a definite

realization that we were doing something important. There

was a sense that we were not part of some money-making

machine. We were not here for that. In fact, many of us

did not expect that the movie would make much money; we

thought we were making a contribution to film. As

pretentious as it may sound, we truly believed that we

were doing something artistically important. So there was

something more in our thoughts than just doing our jobs.

Michael Hausman made us feel like we were doing something

important. He was the best kind of leader. That’s

what I learned. Yes, I learned about leadership.

7

Ang Lee?

Because Michael Hausman was the producer

he was, Ang Lee left the non-artistic matters to him. Of

course, Michael always consulted with Ang, but Ang did

not have to worry about production issues because Michael

took care of them. And Michael always consulted with

others—Diana Ossana, Tom Benz, and so forth—in

making those decisions. He held meetings with everyone;

everyone was part of the effort.

That way, Ang Lee was able to concentrate

on performance, story, visuals—all of the things a

director should do. He didn’t get caught up on

production, technical, and budgetary things that tend to

be distracting.

Ang Lee was really very firm about what

he wanted. He was always quite clear about his

expectations, then he let Michael Hausman take the reins

as the guy out front. Michael “led the charge.”

Because Ang was so clear about what he wanted, I learned

that if you are doing your job as an assistant director,

the director won’t be distracted. If you do your

best as an assistant director, a good director will give

you his best. Ang Lee is the standard of what a good

director should be.

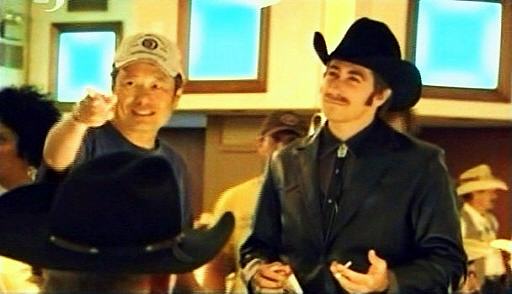

“Ang Lee was really very firm about what he

wanted.”

Childress Dance Hall Calgary, AB

I read that Ang Lee said in many films he

had to be a director who pulled people along, but in

making Brokeback Mountain he felt as if he was

being pushed along by the crew. There is some truth to

that. That is ultimately what you want to happen. It

speaks to him as a person, and as a professional, that we

wanted to do that for him; that we felt the desire to

support him, and his creative spirit, in every way.

8

Scott Ferguson?

Again, it was very educational to work

with him. I’ll tell you a story. When he first

handed me the schedule and started to talk about it, I

asked him questions. He did not have a copy of the

schedule in front of him. I asked questions about days I

thought might be too light, or too heavy, or where travel

between locations might pose problems. It was amazing; he

was discussing it without anything in front of him. He

had absolute knowledge of the material, a detailed

document some 20 pages long covering some 50 days of

shooting, hundreds of scenes, all across the province; it

was all in his head. And he knew it all cold.

And scheduling was just one of Scott

Ferguson’s enormous responsibilities. He worked with

Michael Hausman on the budget. Primarily the budget and

negotiating with the unions. He also negotiated with the

park authorities to get permission to bring domestic

sheep into the parks, which is completely illegal for

good reason. I don’t know if you are aware of this

but domestic sheep carry diseases that kill Rocky

Mountain sheep, and there were many long negotiations

over that issue. All of that was Scott’s

responsibility, along with Murray Ord, who is a local

producer. It was a challenge to get that access.

Scott’s ability to manage and retain

huge amounts of detailed information, and yet be an

incredibly personable guy, taught me that a great

production manager or assistant director should have

complete knowledge of the show. Scott had complete

knowledge of the show. Michael Hausman had complete

confidence in him, as he should. Scott Ferguson is among

the most capable production managers I have ever

encountered.

Diana Ossana?

First of all, she is a joy to work with. Brokeback

Mountain was not the first opportunity I had to work

with her; I had met her on a small miniseries that they

made here, Johnson County War. I had a smaller

role in that; I just helped with second unit.

Diana Ossana was so great in keeping us

focused on the story. I hope that we didn’t need too

much reminding, but that was her role. Whenever there was

a change that needed to be made it was done very smoothly

and, of course, the craftsmanship was unparalleled. I say

that not only from a creative perspective—she is a

superlative writer—but also from a production

standpoint. Pages came out in an efficient manner; she

has a good knowledge, an excellent knowledge, of

production.

Oftentimes there are problems in

production. You do not have access to a certain location,

or certain actors are not available; it happens. Some

writers do not understand the production implications of

what they are writing. They will respond to a problem by

writing something that makes a situation even worse. But

Diana is not like that. She has an excellent production

background so she will rewrite a scene that both makes

the story better and also helps production. We admire her

quite a bit around here. She is one of our favorite

people; I hope that she comes back.

9

“She is a joy to work with.”

Diana Ossana at Cassie’s Bar Fort

Macleod, AB

Rodrigo Prieto?

He’s one of the finest people I have

ever worked with: a gentleman, incredibly talented,

soft-spoken, down to earth, approachable. You won’t

find anyone who will have anything other than the highest

praise for him as a person or as a cinematographer. What

else can I say?

You know the scene in the Mexican Alley,

which we teased him about—he was happy to do it! To

have that lack of ego and be willing to go to that extent

to make a contribution to the film, recognizing that he

had already made a massive contribution to the film, it

is astounding. He is a remarkable person in every way. I

wish he would come back to Alberta.

His technical knowledge is said to be

extensive.

You are right. To his credit, Rodrigo

Prieto has publically acknowledged the beauty of the

Alberta locations, but he did not give himself nearly

enough credit for the difficult job he had to do. There

were distinctive technical things about that film. So

much of it was shot outdoors, meaning that there were

different kinds of challenges involved than there are in

a film which is mostly made inside the studio. And there

are issues with natural light.

Natural light can be a very difficult

thing for a director of photography to deal with,

especially in the summer in Alberta. You may have noticed

how quickly the weather can change here. Of course, you

could be shooting a scene for a day, or two days, but you

must match the sky light for a scene which will be on the

screen for only a minute or two. So that becomes the

director of photography’s issue. The sun will be

passing through the sky, and I remember specifically that

we often encountered clouds. Inconsistent clouds.

10

Consistent clouds can be fine, because

they alleviate the problem of varying brightness and

shadows as the sun passes among the clouds. But,

unfortunately, we did not have those. The clouds would

pass in front of the sun, and I remember specifically

many times at the Goat Creek campsite [Campsite #2] when

we had to wait for clouds to shoot.

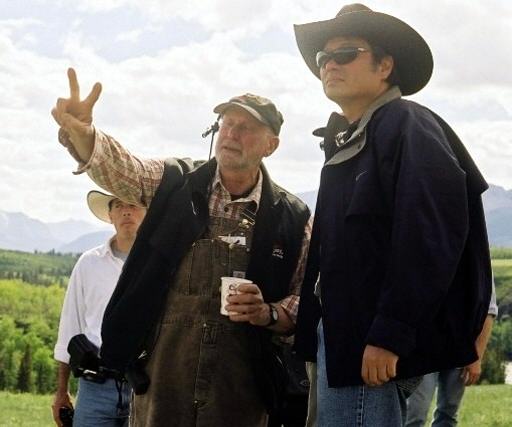

“A gentleman, incredibly talented, soft-spoken,

down to earth, approachable.”

Prieto with Lee at Campsite #2 Spray Valley

Provincial Park AB

Sometimes we would even do two versions,

one in the clouds and one in the sun. Then we’d wait

to see which version we had to match! That was very hard

on the actors because they had to sustain their

performances under both situations. And, at one point, we

were literally running between two different parts of a

scene, one we had established in clouds, the other we had

shot without clouds in sunlight. Fortunately, at that

point we were shooting with hand-held cameras, so when

the sun came out we would move to the sunny area, and

when it was in the clouds we would rush back to the other

area. It was the only way to move forward with our day.

This kind of thing is very tricky for the director of

photography, the actors, and the director. They all know

what they were doing.

Of course, clouds were not Rodrigo’s

only challenge. When we did the Mexican Alley scene,

which was very elaborate and extensively lit, he was able

to deal with the complexities of that as well!

11

[Script supervisor] Karen Bedard?

I love her; she is fantastic. Script

supervisor—that is a job for which there will never

be any kind of Academy Award, and there absolutely should

be one. A great script supervisor, or continuity person,

will save your keister several times in any movie,

because directors are not necessarily thinking about

continuity in a movie.

But a great script supervisor will also

point out continuity issues in story or performance, and

Karen is at that level; she is one of the top script

supervisors. Directors will trust her to tell them when

scenes might have some kind of incongruity. I am not

referring to just the physical elements, which of course

they will point out as well, but also how actors are

playing a story line.

I’ve known Karen for many years, and

she is incredibly respected by all of the directors for

whom she works, and she has worked with many of them

because they come from all over the world to shoot here.

She is a consummate pro.

Commentators have related the clothing

patterns and colors to themes in the story. Yet there is

nothing in the script itself about the clothing.

The people who were involved in that

decision were Marit Allen [costume designer] and Ang Lee.

Ang would probably inform the creative people, but they

would be the only people, other than the actors, of

course, who would know why they are wearing those colors.

I wouldn’t assume that those are all

conscious choices. It could be a case of people infusing

things into the film that are not there, though that does

not mean that it did not happen. This issue arises in all

artistic criticism. I was a student of film criticism

early in my career, until I realized that sometimes

people put too much faith in the filmmaker, crediting him

with incredibly deep decisions when really, much of the

time, what appears in the film is simply what looks best.

It may not have to do with the story, just that it looks

good.

Brokeback Costume Designer Marit Allen

Childress Rodeo Rockyford, AB

That having been said, a director chooses

a color palette for the scenes in a film. The director,

the director of photography, the production designer, and

the costume designer all engage in very serious

discussions and decisions about colors. For instance,

Mexico obviously required a different color palette than,

say, the rodeo or the dance hall sequences. They are very

specific about choosing those colors, and, because Brokeback

Mountain is a movie of many individual frames, they

are very conscious of the ways in which colors are used

in those frames. You can never know with certainty, but

Ang Lee is a real artist. He may have gone that deep, but

I never heard any discussion about that.

12

|